The Cow Barn

The Cow Barn, shown largely completed, in the October 1912 issue of The Craftsman. Dirt, probably from the excavation, can be seen piled on the right hand side of the photograph and–tellingly–there is no trace of the Milk House which we believe was built probably during the Farny era in two separate phases.

The Cow Barn was largely completed by the summer or early fall of 1912, as photographs published in the November 1912 issue of The Craftsman attest. Along with the Horse Barn, that was built concurrently, this impressive structure helped anchor the agricultural core of the farm and removed the animals–with their attendent smells, sounds, and the work of keeping them–away from the family.

Built into the hillside, the barn is largest of the agricultural buildings, which makes sense because Stickley had relatively few horses and a larger number of cows. The design is, to put it gently, unconventional: it does not conform by and large to the plans of contemporary cow barns and no convincing precedent has been located. At the rear of the barn, the space moved from a single-story structure to two stories, with two large rooms that were separated by a central silo. The silo would have been accessed by a farm road in the back, but access to–and indeed the purpose of–those adjacent rooms remains a mystery. The chimney on the right hand side of the photograph still stands, and served a fireplace that Stickley installed as a way of keeping the space warm and reducing humidity. This, combined with adequate ventilation, provided two of the "many innovations for the health and comfort of the animals" spoken of in The Craftsman.

More than just a component in the working aspect of Craftsman Farms, the herd was used to bolster Stickley's identity because it tied him intimately to the land. The herd, of which he was understandably proud, produced milk, butter, and cream for Stickley's Craftsman Restaurant and thus gave the Craftsman Building in Manhattan a connection to the land and the attendant associations that came with that. More than just an anonymous 12-story building plopped into Manhattan, there was a connection to farming, a real sense of place, and the intimate involvement of Stickley himself. This may explain in part the two-page spread the magazine devoted to the cows in October of 1912 and why there were more portraits of the cows than of the family included in The Craftsman. The sense of specificity–of knowing that "Woodcrest Rachel" was a champion producer who averaged 27 quarts a day over a 2-year period–was another way to assert the authenticity of these endeavors. Thinking, perhaps of young George Washington, the first calf born on the property, as you dined in (or dreamed of eating at) the Craftsman Restaurant allowed for a personal connection to an authentic place that was otherwise impossible in the majority of New York City Restaurants in the period.

A photograph of the herd published in the October 1912 issue of The Craftsman. Neither the location of this photograph or the identity of the figure at the right has been identified.

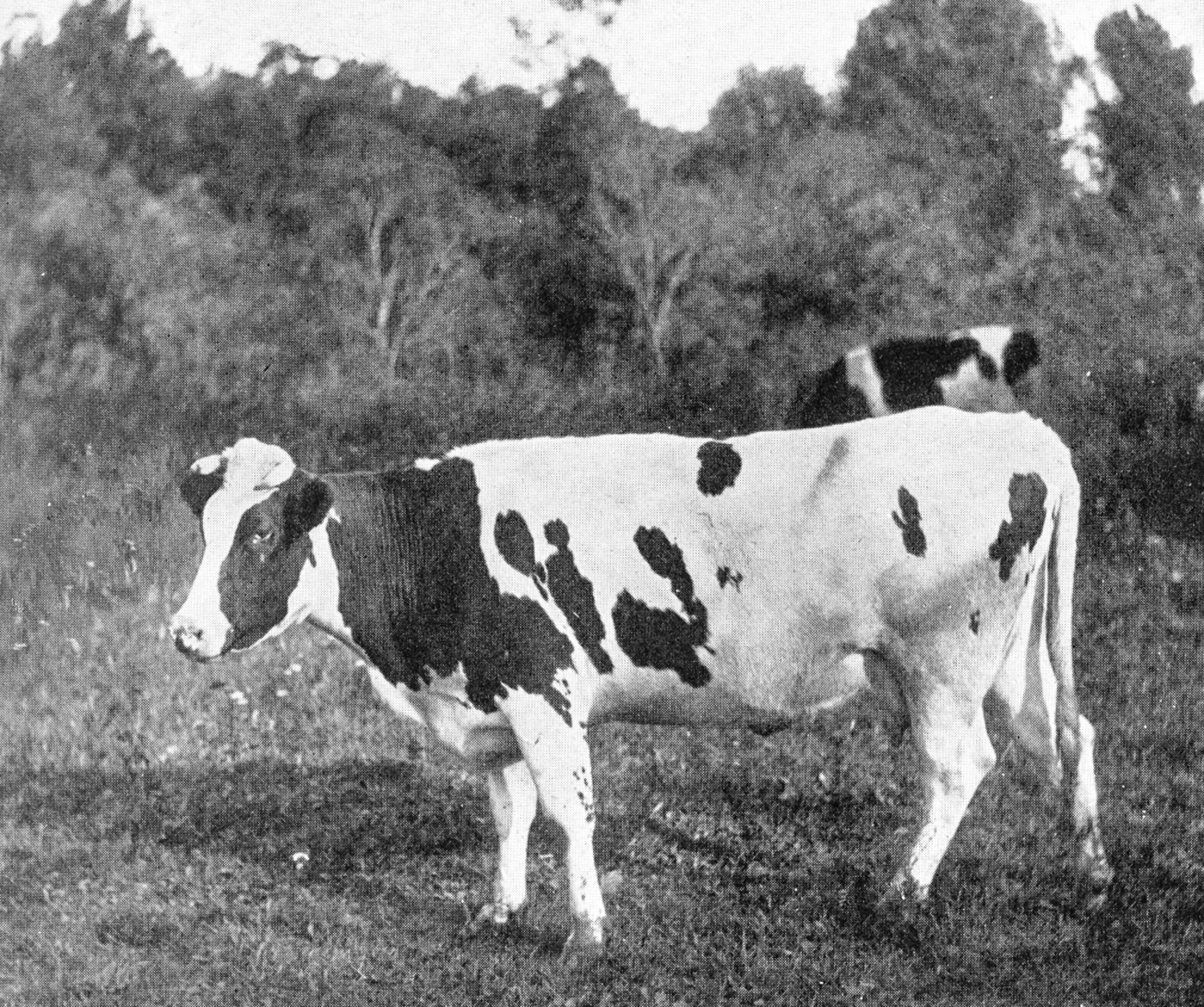

Woodrcrest Rachel, champion producer of dairy, was one of two cows whose portraits appeared in The Craftsman.

Here is young George Washington, the first thoroughbred Holstein calf to be born on the property and so-named because he was born on the former president's birthday. In some ways, this is the marker of the full-blown American dream: a plot of land, a productive farm, and a love of country.

A Conundrum: What Did the Interior of the Cow Barn Look Like?

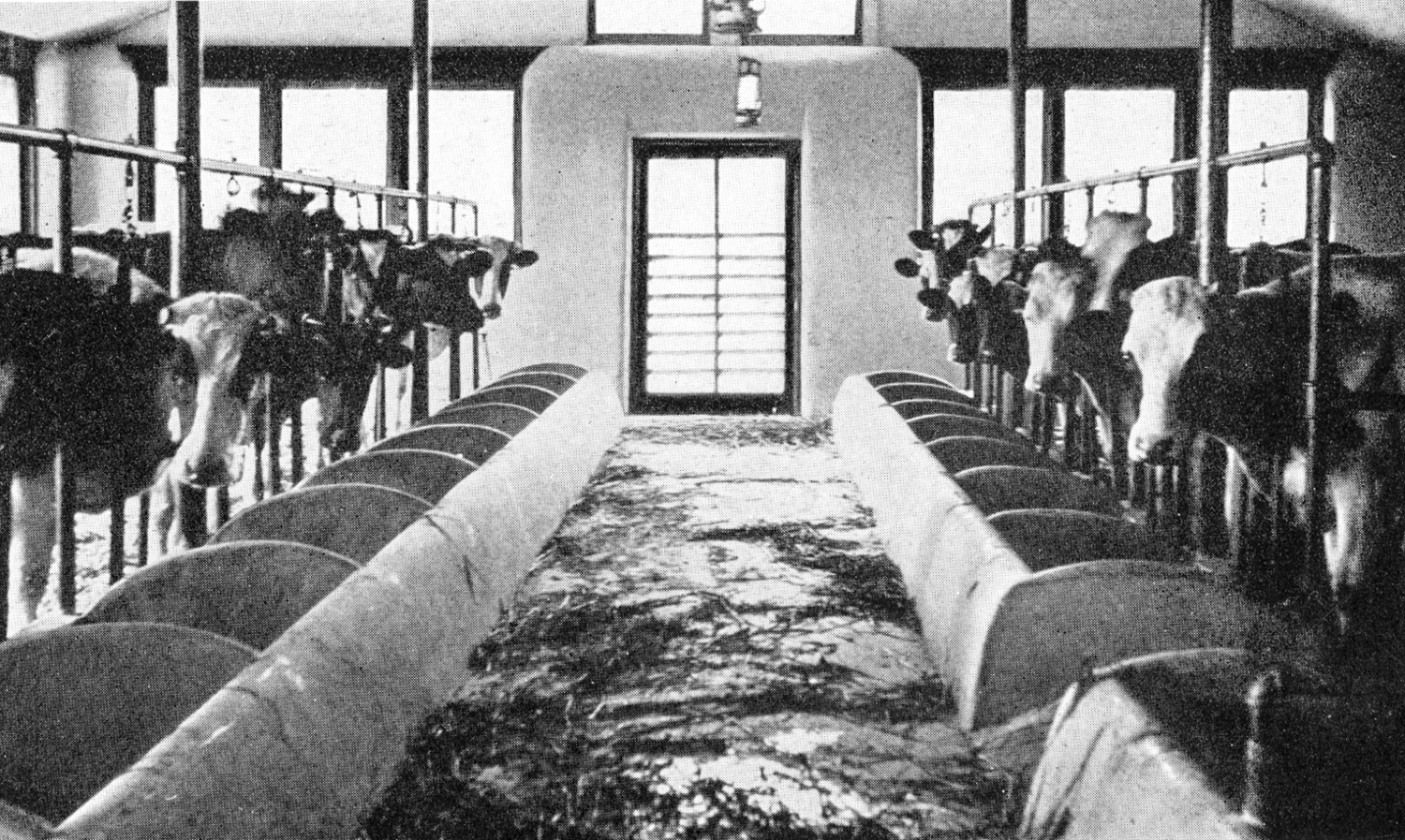

Since the publication of a photo captioned: "The cow stable which Mr. Stickley designed and built: it is finished on the inside with many innovation for the health and comfort of the animals," in the October 1912 issue of The Craftsman, it has been taken for granted the illustration shows the interior of the Cow Barn.

Purported interior of the Cow Barn.

It is one of the things in the magazine that is so plainly stated, that truthfully, there would be little reason such a statement could raise an eyebrow. We know, for instance, that Stickley had a small Holstein herd from numerous sources and the remains of the barn–which tragically was destroyed fire decades ago–still stand. Handsome cows, an enormous barn, case closed.

The real difficulty of the photograph in The Craftsman is that it is impossible to make sense of it in light of either the archaeological record or to square it with photographic record of the exterior. This is troubling, because although only the ruins of the barn remain, we can work out from where the photograph would need to have to be taken to show this view. The Cow Barn had only one bank of windows along the long side of it (facing southerly, towards Route 10) so the photographer must have stood facing west. Indeed, the break in the feeding trough along the right side of the image helps to establish–more or less–what we believe would have been the midway point in a central corridor that ran between the doors at the eastern and western ends. So far, so good. Nothing in the size or positioning of the windows raises any alarm bells.

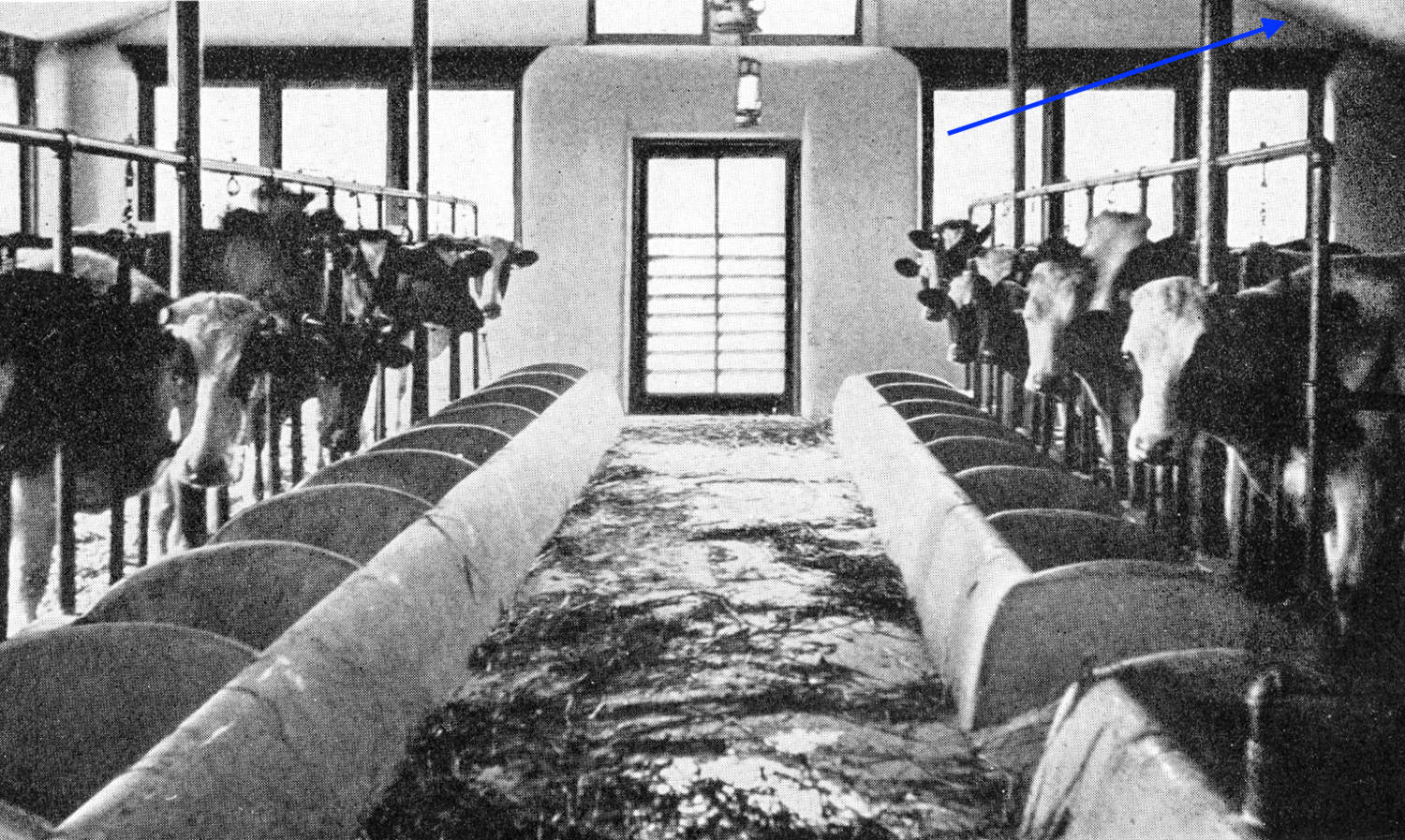

The blue arrow at right points to a descending roof line and indicates a peaked roof of dimensions that the Cow Barn did not have.

The problems begin with the upper right-hand side of the photograph, specifically the ceiling line that indicates a peaked roof with the apex centered over the door. Because the Cow Barn was built into the side of a hill, the roof is a bit more steeply pitched, and the apex does not occur over the doors, but much further back at the chimney. Some have wondered whether this could have been an interior feature not evident from the outside, but this is equally problematic, as we find no traces of a descending ceiling line in the ruins, nor evidence for what could have supported this. Consider too that such a configuration would wreak havoc with the second story rooms at the back of the barn and the suggestion becomes unsustainable. Lastly, which the photograph shows heavy troughs that seem to have been built in to the concrete floor, there is no evidence of anything like this in the ruins of the Cow Barn, nor any indication that similarly shaped troughs not integral to the floor were ever placed there. As for the supports shown in The Craftsman photograph, the sleek metal posts are elegant and structural, but not like anything we see in the Cow Barn. At numerous spots on the concrete floor are clear post holes in the concrete, voids that once held large timbers used to support the roof, and it is the obvious lack of rustic timbers in The Craftsman photograph that seals its fate: while this barn may have been an inspiration for Stickley's Cow Barn interior, it is not the barn he built.

The remains of numerous post holes are still evident in the floor of the barn. Based on the location of this one, we should see a large timber support member in the interior photograph of Stickley's Cow Barn. Unfortunately, there is none.